Because the aroma of scorching meat fills the air on Tsiknopempti, or “Smoky Thursday,” Greeks all over the place put together for a feast steeped in historical past. This annual celebration, held in the course of the Greek Carnival season, is a time to indulge earlier than the fasting of Lent begins. However the custom of coming collectively over grilled meats goes again a lot additional than fashionable road barbecues and your native souvlatzidiko (purveyors of the beloved meat on a skewer, souvlaki) – it reaches deep into the spiritual, social, and even athletic lifetime of historic Greece.

So, how did the Greeks of antiquity devour meat? Was it an on a regular basis staple or a sacred luxurious? And what would a Homeric hero, an Olympian wrestler, or a Pythagorean thinker consider our modern-day feasting? Let’s take a journey by means of the rituals, banquets, and even fast-food tradition of the traditional Greek world.

Feasting with the Gods

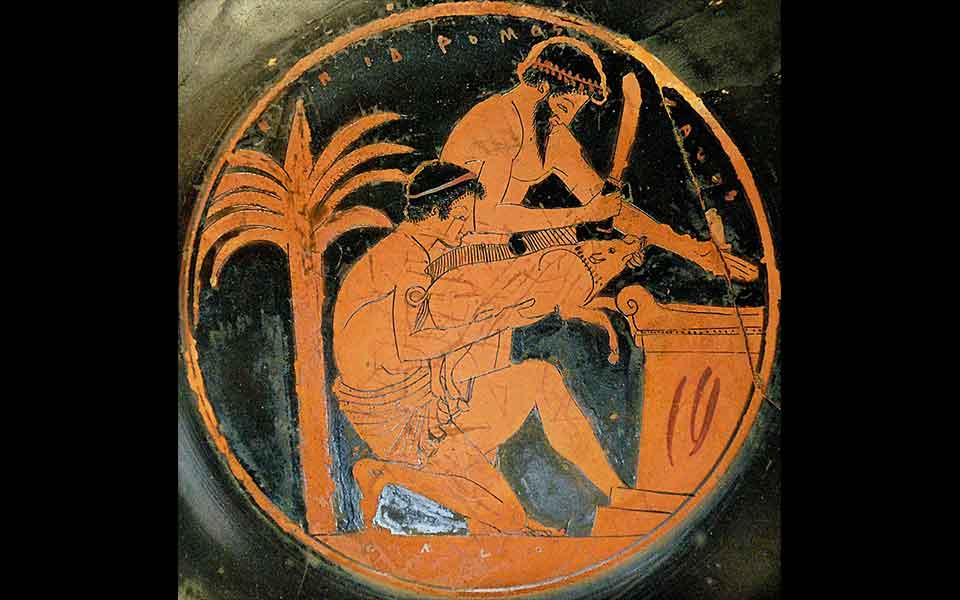

In historic Greece, meat was extra than simply meals – it was a divine present, a conduit between mortals and the gods. The commonest method for a Greek to eat meat was by means of spiritual sacrifice, referred to as “thysia.”

A typical sacrifice concerned slaughtering an animal – typically a cow, pig, sheep, or goat – and providing the gods their share. The method was meticulous: the animal was consecrated, its throat slit, and choose bones, akin to thigh bones and tail vertebrae, had been burned on the altar, sending up aromatic smoke (“knise”) to the heavens. As the Greek poet Hesiod (fl. c. 700 BC) recounts in “Works and Days,” this follow started with Prometheus’ trick on Zeus, when he wrapped bones in glistening fats:

“From that point, males have burned white bones to the immortals on aromatic altars.” (Works and Days, 47–49)

After the gods acquired their portion, the remaining meat was cooked and shared among the many worshippers. These sacrificial feasts had been extra than simply meals – they bolstered social bonds and hierarchies, with prime cuts reserved for elites or clergymen, whereas the remainder was divided amongst members. The historian Herodotus (c. 484–c. 425 BC) notes that in Sparta, meat from sacrifices was allotted based mostly on civic rank (Histories 6.56), making certain that meals distribution mirrored societal construction.

However what about meat that wasn’t a part of a sacrifice?

© Shutterstock

Past the Altar

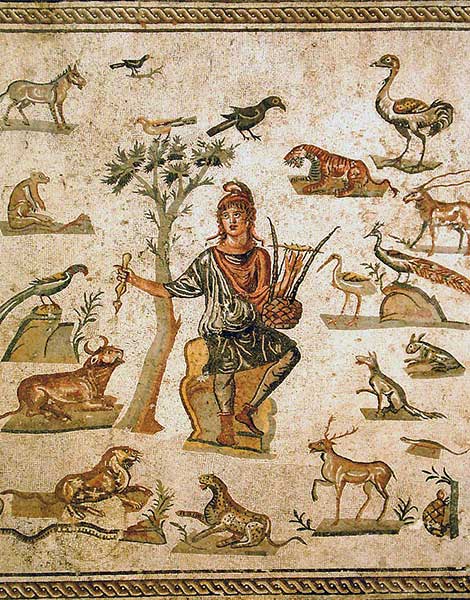

Though spiritual sacrifice was essentially the most culturally important technique to eat meat in historic Greece, it wasn’t the one one. Osteological proof from numerous archaeological websites signifies that looking offered one other supply of meat, particularly in rural settlements. Wild recreation akin to deer, boar, rabbit, hare, and an assortment of birds (pheasants, partridges, quails, thrushes, blackbirds, geese, and geese) ceaselessly made their technique to Greek tables.

Writing within the 4th century BC, Xenophon describes how wild boars and deer had been hunted at Artemis’ sanctuary in Skillous, within the northwest Peloponnese, the place they had been later roasted and loved throughout spiritual feasts (Anabasis 5.3.37).

Markets additionally performed a job in meat consumption. The thinker and naturalist Theophrastus (c. 371–c. 287 BC), in Characters (9.4), mentions meat being offered within the agora (market) with none reference to sacrifice, suggesting that a industrial meat commerce existed. This means that some historic Greeks may afford to purchase and eat meat exterior of spiritual contexts – although it remained far much less frequent than in fashionable diets.

One other clue to the distinction between sacred and secular meat lies in cooking strategies. In sacrificial feasts, meat was typically boiled, making it uniform and simple to distribute. This aligns with an episode in Homer’s “Odyssey,” the place Odysseus and his crew boil their sacrificial meat moderately than roasting it (Odyssey 3.460–470). In distinction, roasting or grilling, which enhanced taste and texture, was extra frequent in secular meals. Elsewhere in Homer’s epics, warriors are depicted roasting meat on spits – an early model of souvlaki or kontosouvli (giant chunks of spit-roasted pork) as we all know it right this moment!

Meat as Gasoline

Meat wasn’t only for spiritual or communal feasts – it additionally performed a vital function in athletic coaching.

Based on some sources, early Greek athletes adopted principally vegetarian diets, counting on figs, cheese, and barley. However by the Sixth century BC, meat had turn into a key part of an Olympian’s vitamin plan. Wrestlers and boxers, particularly, consumed giant portions of meat and bread to construct muscle, a follow referred to as “compelled vitamin.”

Maybe nobody embodied this meat-heavy eating regimen greater than Milo of Croton (fl. 540–511 BC), a legendary six-time Olympic champion from Magna Graecia. Historical sources declare he ate 20 kilos of meat per day, washed down with copious quantities of wine. Writing within the 1st century BC, Diodorus Siculus describes how Milo wore a lion’s pores and skin and carried a membership, “like Heracles.”

Nonetheless, not everybody authorized of such diets. Writing centuries later, the Greek doctor and thinker Galen (129–c. 216 AD) criticized extreme meat consumption, believing it might be detrimental to well being.

Regardless of the controversy, the connection between meat and power was firmly established, shaping Greek views on vitamin and athleticism for generations.

© Giovanni Dall’Orto / Public area

Vegetarians, Philosophers, and Meat Abstinence

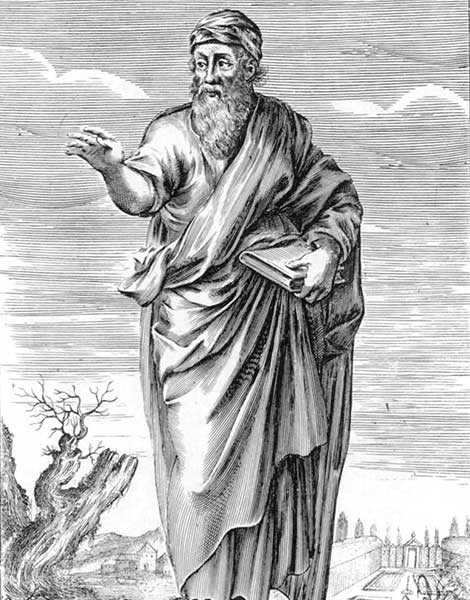

Not all Greeks embraced meat consumption. Sure spiritual and philosophical actions promoted vegetarianism, viewing it as a purer lifestyle.

The Orphics and Pythagoreans, for instance, noticed meat-eating as spiritually impure. Pythagoras, the Sixth-century BC thinker, famously condemned consuming animals, equating it with cannibalism:

“What else is that this however to devour our visitors, and barbarously renew Cyclopean feasts?” (Ovid, Metamorphoses 15.60ff)

He and his followers as a substitute promoted a eating regimen of fruits, grains, and legumes, believing that each one residing beings possessed souls. Although not widespread, such concepts planted the seeds of moral vegetarianism, which might re-emerge in later historic durations.

For extra on the subject of meat abstinence in historic Greece, click on here.

Souvlaki and Sausages on the Go

If you happen to suppose quick meals is a contemporary invention, suppose once more – the traditional Greeks additionally loved fast, handheld meat snacks.

On the Bronze Age settlement of Akrotiri on Santorini, archaeologists found grilling racks and a firebox with a flat griddle, proof of souvlaki-style skewers and pita courting again some 3,700 years.

Homer even describes a dish eerily just like a contemporary sausage, evaluating Odysseus’ stressed sleep to a paunch full of fats and blood, roasting over a hearth:

“…And as when a person earlier than an incredible blazing hearth turns swiftly this manner and {that a} paunch stuffed with fats and blood… desirous to have it roasted shortly, so Odysseus tossed back and forth…” (Odyssey 20.25–30)

Whether or not in a taverna, a market, or at a sacred feast, it appears Greeks have all the time liked their grilled meat.

For extra on the earliest proof for Greece’s most beloved road meals, click on here.

Tsiknopempti: A Trendy Echo of Historical Traditions

Quick ahead to right this moment, and Tsiknopempti continues Greece’s lengthy love affair with grilled meats.

Eleven days earlier than Clear Monday, which marks the beginning of Lent, Greeks collect to feast on meat earlier than the fasting interval begins. Streets, tavernas, and houses fill with the smoky aromas of souvlaki, sausages, and steaks. In actual fact, the title “Tsiknopempti” comes from “tsikna,” which means the savory odor of roasting meat, and “Pempti,” which means Thursday.

In some areas, Tsiknopempti has its personal distinctive customs. In Serres, as an illustration, males leap over barbecue flames as soon as the meat is cooked – a follow believed to convey good luck. On the island of Corfu, locals collect on the town squares for full of life gossip classes, playfully parodying public figures in a practice of lighthearted satire.

Regardless of the millennia of change, one factor stays the identical: meat feasting is a time for group, celebration, and custom.

So, as you’re taking a chunk of juicy souvlaki this Tsiknopempti, bear in mind – you’re not simply having fun with a meal. You’re partaking in a practice that stretches again to Homeric feasts, Olympic champions, and the smoky altars of the gods themselves.

Recent Comments