“Every station will probably be a museum. This can make the Thessaloniki Metro distinctive, in contrast to another rail system on the planet,” proclaimed representatives of the metro’s development firm in 2006, as they signed a memorandum of cooperation with the Greek Ministry of Tradition on the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki. Each side had been properly conscious that the excavations would dig deep into the very bedrock of the town’s wealthy historical past, uncovering treasures that lay buried beneath the streets. Archaeologists had already identified that the metro’s proposed route lined up with the archaeological layers of a metropolis that had been repeatedly inhabited since its founding in 316/315 BC. The one actual query was what surprises the excavations would reveal.

Final weekend, through the inauguration, a various crowd flooded the platforms, collaborating in a quiet celebration. There was no music, no fanfare – solely an otherworldly, virtually ceremonial environment. Smiling faces, exclamations of marvel from younger and outdated alike, and raised telephones that captured the novel expertise of traversing their metropolis in only a few minutes. The vacation spot wasn’t simply the metro itself – although it promised to rework their day by day lives – but additionally the town beneath the town: the open museums. “I don’t see any historic artifacts right here. Let’s go to the station that appears like a museum,” stated a younger man to his pals as they descended the escalator at College Station. Evidently Venizelou has already change into a vacation spot in its personal proper.

© Alexandros Avramidis

Eighteen years after that memorandum was signed, we launched into the journey by means of these “open museums.” Excluding the encapsulated city block at Venizelou Station and the open archaeological house at Aghia Sophia Station, 21 movable artifacts – out of the 300,000 unearthed through the metro’s excavations – are on show within the ticketing areas of three of the road’s 13 stations (Syntrivani, Aghia Sophia, Dimokratias).

Whereas these modest displays don’t but kind full “museums,” the details about the traditional metropolis throughout the partitions – bounded by its two gates, east (Syntrivani) and west (Dimokratias Sq.) – is dense. Concise, well-structured texts, together with quite a few pictures of the excavation websites, supply a window into Thessaloniki’s historical past, emphasizing its 24 centuries of steady habitation, the panorama at every station, the timeless Egnatia Street, and the town’s city evolution from its founding in 316 BC till the Nice Fireplace of 1917.

© Alexandros Avramidis

At Syntrivani Station, fragments of mosaic flooring and wall work from a cemetery basilica (400–500 AD), alongside 4 intricately sculpted marble sarcophagi (100–300 AD), supply a glimpse into the opulent tombs of the japanese cemetery through the Hellenistic and Roman intervals. These displays additionally make clear the Christianization of the necropolis, marked by the development of a worship website later changed by a three-aisle basilica.

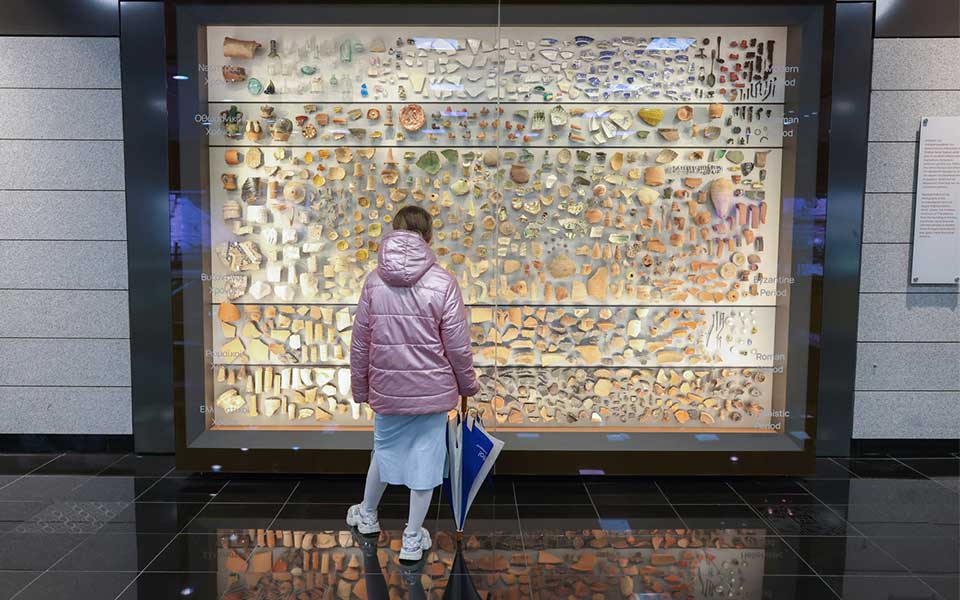

At Aghia Sophia Station, a show of seemingly modest but invaluable artifacts gives perception into the realm’s microhistory. Fragments of oil lamps, amphorae, vessels, glass, and metallic objects – spanning the Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman intervals – alongside objects buried within the ashes of the Nice Fireplace of 1917, vividly depict the town’s stratigraphy from its founding.

© Alexandros Avramidis

Beneath the cover of Aghia Sophia Station’s outside archaeological house, guests are transported to imperial Thessaloniki, a symbolic website flanked by two important Christian basilicas: the Acheiropoietos and the five-aisle episcopal church, positioned on the location of the Church of the Knowledge of God (Aghia Sophia). This timeless crossroads shaped by the Decumanus Maximus (the principal avenue of late antiquity and Byzantine instances) and the cardo (a perpendicular street), a part of a Sixth-century city planning initiative, was the middle of the town’s political and spiritual life.

Guests are guided by means of the preserved architectural stays of late antiquity and the Byzantine interval, with illustrated maps, descriptive texts, and Braille guides that present element into the historic and architectural context of either side of the fashionable Egnatia Road.

© Alexandros Avramidis

At Dimokratias Station, 13 intact amphorae – as soon as used for storing and transporting wine – are neatly stacked on a bench inside an open-air ecclesiastical advanced (450 AD), recreating the bustling industrial panorama of late antiquity (modern-day Vardaris). State warehouses for wine and oil, alongside workshops similar to oil presses, lined the roads connecting the countryside to the Golden Gate. Close by, a putting marble sarcophagus (200–300 AD) from the western cemetery catches the attention. Its engraved inscription reveals {that a} outstanding citizen, Calpurnius Eudemos, constructed the sarcophagus for his “beloved” deceased spouse, providing a poignant glimpse into the private lives of Thessaloniki’s historic inhabitants.

However it’s Venizelou Station that is still the spotlight for many guests. Protecting 1,300 sq. meters, this monumental city advanced showcases the town’s continuity throughout centuries. Guests can discover the location from glass balconies, examine its historic transformations on touchscreens and watch movies and 3D visualizations of Thessaloniki by means of the ages. Beginning in January, organized excursions will permit guests to stroll alongside the monumental street, tracing the evolution of public areas and admiring buildings such because the tetrapylon (a monumental arch on the intersection of the Decumanus maximus) and its semicircular plaza. The workshops and outlets of the Byzantine market – the place East and West as soon as converged – mirror the town’s enduring industrial vitality, which continues to the current day.

This text was beforehand printed in Greek at kathimieri.gr

Recent Comments